Publication

Arizona Court of Appeals “Updates the Handbook” on Judicial Review of Agency Action

When operating a business, it is nearly impossible not to have to interact with state or other local government agencies. Decisions regarding permits, licenses, government contracts, workforce compliance, environmental requirements, and more, can make all the difference to the success or failure of a particular venture. But, after those final agency decisions are determined, those businesses unhappy with the outcome have the opportunity to challenge the determinations — first within the particular agency that made the decision and, eventually, to a court.

For many years, however, this process was criticized for stacking the deck in the government’s favor. For many cases in Arizona, to challenge an administrative action, a regulated party must first request a hearing before an administrative law judge (ALJ) at the Office of Administrative Hearings (OAH). After the ALJ issues a decision, the agency head can accept, reject, or modify it in issuing its final decision. Subsequently, the regulated party may file an appeal in a superior court. Although these procedures are intended to safeguard the due process rights of the regulated party, courts would often defer to a governmental agency’s legal interpretation of a statute and the factual determinations that the governmental agency made, to justify the particular action under consideration.

Responding to these criticisms, in 2018, the Arizona Legislature amended A.R.S. § 12-910 to prohibit deference to agencies’ legal interpretations. Then, in 2021, the Legislature again amended the statute, this time to prohibit deference to agencies’ factual determinations. With these amendments now in effect, the statute specifically directs courts in all proceedings “brought by or against the regulated party” to “decide all questions of law, including the interpretation of a constitutional or statutory provision or a rule adopted by an agency,” and “all questions of fact” without deferring “to any previous determination that may have been made on the question by the agency.” A.R.S. 12-910(F).

Until recently, however, the amendments to A.R.S. 12-910(F) had not been fully fleshed out by the courts. In Simms v. Simms, the Court of Appeals has now provided regulated parties an updated “handbook” regarding judicial review of agency action.

Under Simms, courts can no longer defer to agencies’ legal interpretations, even if the interpretation is longstanding and undisturbed. Courts also must no longer defer to agencies’ resolution of discrete factual issues. After conducting a truly independent review of the legal and factual questions in the agency’s final decision, the court asks whether the agency’s final decision (the order from the agency’s head accepting, rejecting, or modifying the ALJ’s decision) provides substantial evidence for the particular agency action under consideration. However, the evaluation of whether the substantial evidence bar is met still provides a court significant latitude in adjudicating administrative appeals.

For example, although witness credibility is a question of fact, the Court further noted in Simms that appellate courts are ill-situated to make credibility findings on a cold record and that doing so could violate due process. Thus, if an agency modifies an ALJ’s credibility finding or makes its own without hearing live testimony, then the reviewing court still must defer to the ALJ’s finding unless it is clearly in error.

Finally, reviewing courts may defer to agencies’ exercise of discretion and expertise regarding non-legal and non-factual matters. By way of example, the Simms Court explained that the Arizona Racing Commission has discretion to approve or deny a permit to hold a racing meeting if approving the permit “in the locality set out in the application is not in the public interest or convenience.” Under A.R.S. 12-910(F), a regulated party challenged the Commission’s decision to grant a permit that it determined to not be in the public interest, the reviewing court could not defer to the Commission’s legal interpretations (e.g, the Commission’s interpretation of the phrase “public interest”); the Commission’s factual findings (e.g., the Commission’s findings about the locality); or the Commission’s application of law to facts. But the reviewing court could defer to the Commission’s exercise of its discretion to grant the permit.

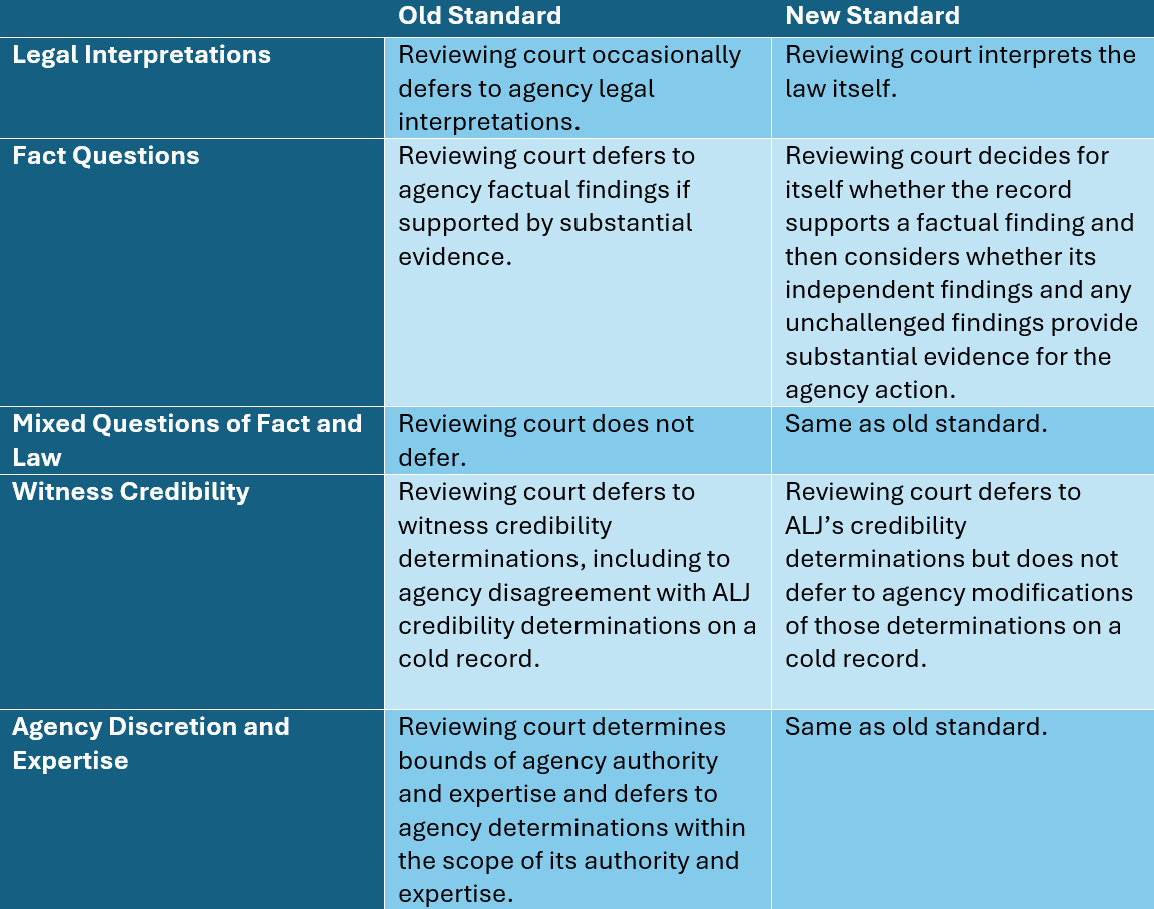

In sum, as articulated by the Simms Court, the amendments to A.R.S. 12-910(F) change judicial review of agency action as follows:

Simms has important lessons for judicial review of agency actions going forward. While courts no longer defer to an agency’s resolution of legal or factual questions, litigants challenging a particular agency action still must point out to the court the specific conclusions they are challenging and explain how the agency erred. The Simms Court twice pointed out that a “regulated party challenging agency action must identify those factual findings with which it disagrees and explain why” to even create a “question of fact” in the first place.

And those unchallenged conclusions may be considered by the court in assessing whether the agency action is “contrary to law, is not supported by the evidence, is arbitrary and capricious or is an abuse of discretion.” Challengers would do well to heed the Simms Court’s warning, identify the agency conclusions that undergird the agency’s decision and create a clear record sufficient to allow the court to find differently than the agency did.

More notably, the framework articulated by the Simms Court will likely increase the frequency with which a court will disagree with an agency’s final determination that parts ways with an ALJ’s initial determination as to the facts and credibility of witnesses. This reality is especially so when the final determination reverses the ALJ’s credibility findings without the benefit of live witness testimony.

Indeed, the closing sentences of Simms highlight the Court’s concern over how the administrative appeal process played out between the ALJ’s initial decision and the agency’s final determination as to the evaluation of credibility. To that end, agencies may be more likely to defer to the ALJ’s determinations regarding the credibility of witnesses and fact questions when rendering the final determination or hear live testimony (or further dissect the transcripts) more often before doing so (and those seeking reversal of ALJ credibility determinations within the agency should consider specifically requesting that the agency hear live testimony).

However, other questions may still need to be sorted out in a further appeal. For example, the Simms Court still left room for courts to defer to agency actions within the scope of their statutory discretion and expertise. With the end of Chevron deference in the federal courts, the Arizona Supreme Court may well follow suit and further tighten the restrictions on and deference to agency authority, even when that agency has the specialized knowledge about the underlying technical issue.

Going forward, in both the federal and state context, it is important for businesses to review proposed new regulations, determine the impact, and provide official comment to those proposals. First, the comments may change the regulation, or, the comments at least become part of the record in the event that a dispute arises in the future. In addition, if a dispute does go forward, businesses should have a plan in place as to how to interact with the agency from the beginning and ensuring all interactions are documented. This will then be the record that is evaluated by the ALJ and the court down the line. If a record is not properly kept, it is more difficult for the court to evaluate the agency’s determination.

About Snell & Wilmer

Founded in 1938, Snell & Wilmer is a full-service business law firm with more than 500 attorneys practicing in 17 locations throughout the United States and in Mexico, including Los Angeles, Orange County, Palo Alto and San Diego, California; Phoenix and Tucson, Arizona; Denver, Colorado; Washington, D.C.; Boise, Idaho; Las Vegas and Reno, Nevada; Albuquerque, New Mexico; Portland, Oregon; Dallas, Texas; Salt Lake City, Utah; Seattle, Washington; and Los Cabos, Mexico. The firm represents clients ranging from large, publicly traded corporations to small businesses, individuals and entrepreneurs. For more information, visit swlaw.com.